One of the best books I read last year was Shift Happens: The History of Labor in the United States by J. Albert Mann (HarperCollins, 2024, 416 pages). A couple things stood out for me: the discouragingly slow process of the labor movement, where protests have too often been met with violent suppression, and the similarity of stories of low wages, long hours, wealth inequality, and immigrants accused of “stealing” jobs, all of which still resonate today.

In my research into resistance movements for this blog, I learned that what’s generally acknowledged to be the first industrial strike in the U.S. took place not far from me, in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. In May, 1824, the mill owners there announced that they were instituting longer hours with a 25% wage cut. Two days later, 100 women walked off the job, soon joined by other workers in a strike that lasted a week. Unfortunately, there’s no record of the settlement, but the workers returned to their jobs on June 3.

The Blackstone River, which runs from Worcester, Massachusetts to the Naragansett Bay, powered the first cotton mills in the United States, bringing England’s industrial revolution to the New World. I decided to head to Rhode Island to see what I could learn about the workers in these mills in time for Labor Day.

The man who started it all was Samuel Slater, an industrialist born in England in 1768 who served as an apprentice in a British textile mill where he memorized the factory design, immigrated to America, and built his mill in Rhode Island. At the time, it was illegal in England to export their textile technology to another country, so Slater is known as “Father of the American Industrial Revolution” or :”Slater the Traitor” depending on which side of the Atlantic you’re on.

The Old Slater Mill is open for tours, part of the Blackstone River Valley Historical Park. I started my tour at the visitor center there, where I read about the history of the area beginning with the Wampanoag, Nipmuc, and Narragansett people and continuing through Roger Williams’ arrival, the early days as an ironworks, and the textile mill heyday which gradually declined when the steam engine replaced water power.

There’s information about child labor, immigration, and Slatersville, America’s first company town, but not much on the labor movement in general or the 1824 strike in particular. I watched an eight-minute video, and while the lives of workers are described–mill stores where they were expected to buy on credit; churches where they were expected to attend weekly services to learn about timeliness, obedience, and sobriety; and child labor that began in the earliest days of the mill–there wasn’t much about how people pushed back for more rights. There was a brief mention of the 1824 strike, “one of the first by female workers,” and the fact that it led to other actions, but no details.

Slater’s mill is across the street from the visitors’ center, and although I didn’t take the guided tour of Slater’s mill, I watched another short film shown at the entrance. The emphasis was on the mill history and how the machinery worked, but there was an interesting mention of the connection to slavery. 25% of the cotton grown in the southern states went to New England’s textile mills, but Black workers were for the most part excluded from mill jobs. I did find this coloring page that tells a little about the 1824 strike!

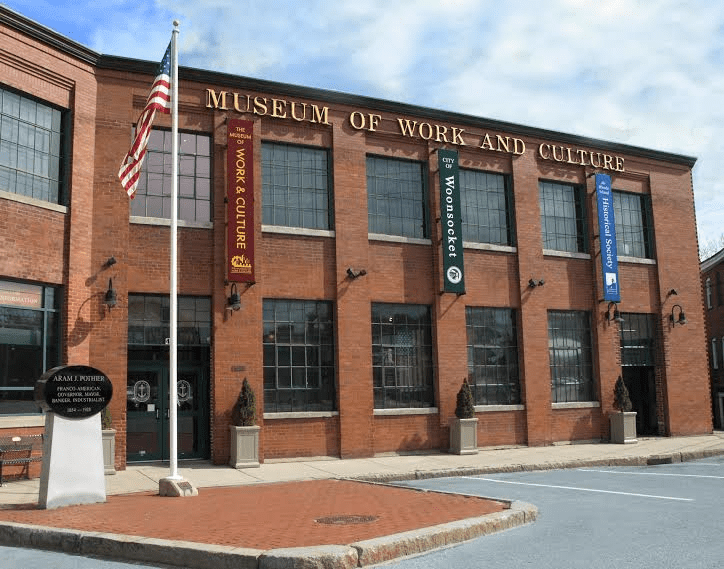

From there I drove about 25 minutes to the Museum of Work and Culture in Woonsocket, where the emphasis was much more on the workers from the area mills, especially those who immigrated from Quebec. “La Survivance” was their name for cultural survival, and this is shown at the museum through replicas of a Quebec farmhouse that people left behind, and a church, a Catholic school room, and the mill floor from their new home.

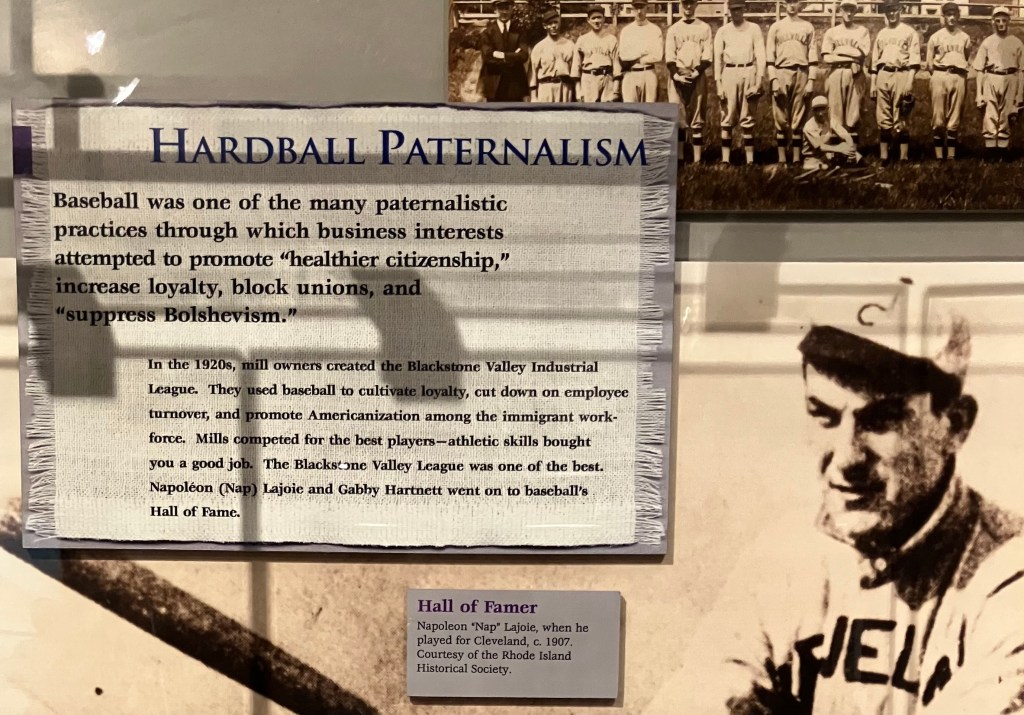

There’s lots of information about working conditions, including child labor, and some of the ways companies tried to keep workers from unionizing, like organizing baseball teams to “promote ‘healthier citizenship,’ increase loyalty, block unions and ‘suppress Bolshevism.'” And there’s a whole room devoted to the history of the Independent Textile Union (ITU) that was organized in Woonsocket during the early years of the Great Depression.

These two museums gave me a taste of the Blackstone Valley’s history, and as I drove home, I was more aware of condo complexes and shopping centers that appeared to be converted mills, as well as the triple decker homes that were originally built to efficiently house workers. The whole area is called the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor, and there’s more industrial history to explore as well as lots of outdoor activities in and along the river.

Books to read

A couple years ago I put together a Labor Day list of books that celebrate workers from different times and places. They’re all books that I’ve reviewed on my other blog A Kids Book a Day, and I’ve tried to keep the list updated.

One more that’s specific to the area is Mill by David Macaulay (Clarion Books, 1989, 128 pages). Macaulay lived in Rhode Island when he created this book and spent a year researching and studying the old textile mills there. He’s created stories about three fictional mills, and his trademark detailed illustrations will show you all you need to know about how they were constructed and operated.